Do More with Less (Noise) - Part 2 of 3

“Well, he responded to the invite as tentative”, Rebecca replied to Joe’s question. It was 10:06. This meeting was the final chance to discuss some options before a final decision was made on the project. Sam said “We’ve been prepping for this conversation for a couple of days and we’re ready to go“. Jasmine declared, “Look, I know we need to have this sorted out today but I’m also double booked so if Harold isn’t here in 2 minutes I’ll have to leave.” Everyone looked uncomfortably at each other around the virtual table. Several minutes passed and Jasmine apologized and then disappeared from everyone’s screen. Seconds later, Harold’s hurried face appeared. “Sorry I’m late, wasn’t sure if I was going to be able to make it, but here I am.” he uttered sheepishly. “So Sam and Jasmine, what have you arrived at?”, he asked. “We just lost Jasmine but Sam can go over his presentation” Rebecca replied. Sam looked annoyed, “Well I can go over this, but without Jasmine here, we’re going to have to reconvene to make this decision”. “What does everyone’s calendar look like this afternoon?”

Sound familiar?

In my last post I discussed the notion that ‘Do more with less’ is made difficult due to the noise within organizations. The noise, I contend, has two main sources: context switching due to multi-tasking, and a lack of explicit communication conventions. This post will focus on the latter.

In Your Organization

What happens if:

a meeting occurs for which your input is required to make a decision and the other attendees are not confident you will attend even though you have accepted the invite?

you neglect, for 4 days, to read an email you were CC’d on?

you receive a meeting invite when you’re already booked?

someone decides to use email for conversations?

you allow yourself to be triple booked and don’t let people know until an hour beforehand which meeting you will attend?

outcomes from meetings are not published?

you receive a meeting invite with no agenda or desired outcome?

These are just a few examples of potential communication failures. If everyone has different expectations or answers to these types of questions, does it matter? I contend it matters a great deal. Not having agreed-upon communication conventions increases the noise in the system and incurs daily costs of delay and more context switching, which in turn lengthens time-to-value.

Lack of Explicit Communication Conventions

‘Conventions’ represent a collection of agreed upon actions, and interpretation of those actions. It’s a system that you can rely upon to ensure your communication is properly interpreted, and to coordinate your activities and collaboration. Imagine what would happen in traffic if every driver, coming upon these signs, interpreted them differently:

For any initiative at work that involves collaboration, a lack of explicit and agreed-upon communication conventions causes numerous delays, which in turn cause more context switching. Those delays (ie. costs) are compounded for every extra initiative you are involved in. Unlike the rules of the road, most people have never been taught how to effectively use email or shared calendars. Further, when someone new arrives at an organization they likely bring an ingrained communication culture from a previous employer that looks nothing like the one they have just joined. If the signals and signs that make up the communication cultures are not explicitly discussed, accidents and traffic jams are the likely result, and days, weeks, and months can be lost to the noise.

Impact of the Noise

In a 2016 post “Clash of Cultures” I wrote about coaching two organizations that had to collaborate to succeed.

“… these (two) organizations also had vastly different meeting cultures. Company A was protective of their peoples’ time. Meetings were scheduled only when required participants were available and there was rigour around responding to meeting invites in order to make the best use of everyone’s time. Company B had a culture where meetings were scheduled regardless of whether required participants were already booked. Further, people who were double or triple booked then selected the meeting they would attend in real-time. This resulted in the meeting organizer never really knowing who would show up for the meeting until it occurred.”

As you can imagine, not knowing who would show up at important meetings routinely made it impossible to meet objectives, and the costs (direct and opportunity) due to rescheduling and delay were enormous. While this extreme example is between two organizations, the same types of differences exist within an organization between individuals and teams.

In large organizations, the proliferation of tools like Slack and Teams has decreased the use of email. This has had positive and negative impacts on communication. Email is a decent tool to record decisions and outcomes. It was never a good tool for having conversations. More synchronous forms of communication (Slack, text) get closer to the experience of a face-to-face conversation, but have unfortunately exacerbated the ‘attention stealing’ and context switching that comes with instant notifications constantly interrupting other trains of thought. Failure to set up conventions (expectations) around electronic communication can lead to false assumptions, wasted time, and the resulting frustration. Just as it’s good to know what it means to be CC’d on an email (and the accompanying attention and reply expectations), it might also be useful to understand the difference between sending a direct Slack channel message or a text message. Why might that be useful? Because in the daily flood of communications we receive, we need to be able to prioritize where we spend our time and attention.

In the end, much of this is about respecting EVERYONE’s time. Not just respecting time in proportion to someone’s level in the organization.

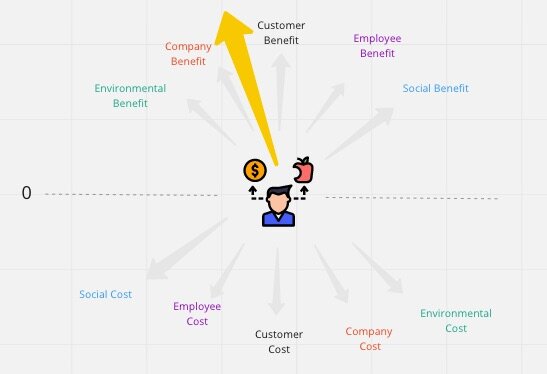

Our Communication Paths are a Network

The myriad of meetings, emails, Slacks, texts, chats, and F2F conversations we have at work form a network. Just as with a computer network, each participant in that network has a fixed capacity. In IT, one of the tools used to protect the capacity of a server on a network is to use protocols. While there can be an overwhelming amount of traffic on the network coming into a server, that server protects itself by only accepting and processing communication with specific protocols. Other forms of traffic, which it considers noise, are dropped and there is not an expectation to respond. In some cases the traffic coming into a server is voluminous enough to cause communications of the appropriate protocol to be dropped. In severe cases an overload of traffic can cause the server to collapse.

In the absence of agreed upon protocols, it is not surprising that information gets dropped and the efficiency of the network degrades. Perhaps you can also see that even with protocols in place your capacity might be exceeded? This is the reality for most people.

What have Organizations been Trying?

There are a myriad of apps and add-ons that aim to help people cope with email and meeting overload. Back in 2008, Google Lab’s Gmail experimental feature titled “Email Addict” prompted you to take a break from your email for 15 minutes. For a very long time Microsoft Outlook allowed you to accept meetings without letting anyone know! These days Microsoft Outlook has instrumentation and prompts that bring to your attention the time you spend collaborating (time in meetings) vs your time available to focus. As we’ve already discussed, meetings do not necessarily equate to effective collaboration. Lots of organizations make proclamations of ‘zero meeting Fridays’ or ‘zero email Fridays. I’ve rarely seen those initiatives respected. There is too much pressure for individuals to make time. I think those initiatives are attempting to solve the wrong problem. The question we should be asking ourselves is WHY we might need a ‘zero email/meeting’ day?!

The trouble is that these tools do not come prepackaged with an accompanying organizational cultural shift. If the system still promotes / rewards individual ‘resource utilization’ the tools will never be successful. They can, however, be useful as a diagnostic to quantify the severity of the noise disorder.

This recent article in the New Yorker, describes the mental and physical costs of email overload, and Arianna Huffington’s innovative approach to email for her employees while they are on holiday. Essentially any email ‘received’ during holiday time is deleted, and the sender is notified that the intended recipient will not receive the email and to please resend in X weeks if still appropriate. This is a terrific solution to the problem of people not disconnecting while they are on holidays. We need similar solutions for the rest of the year so that people have ample time be productive, rather than simply busy.

In his book Collaborative Intelligence, Richard Hackman (Harvard professor of social and organizational psychology) sets out six basic conditions that leaders of organizations must fulfill in order to create and maintain effective teams. I mentioned 1,2, and 3 last week in the discussion of the costs of multi-team membership and context switching. This week let’s look at 4 and 5.

4) Establish Clear Norms of Conduct. Clear ground rules for how members expect each other to behave helps create a collaborative and effective team culture

5) Provide Organizational Supports for Teamwork. The organizational context (e.g. compensation/incentive system, the HR system, and the information system) must facilitate, and certainly not detract from, teamwork.

Establishing clear norms of conduct includes setting organization-wide communication conventions as well as team-specific ones. These are not likely to remain static, but will by necessity evolve as contexts evolve. Reinforcing, sustaining, and modifying them is part of the committment to respecting people’s time.

Providing organizational support for teamwork includes providing access to information, technical and educational support, reinforcement and recognition, and material resources. It also means protecting the team from noise and distraction. This would include setting up organizational norms for how people OUTSIDE the team might best interact with the team.

So What to Do?

For Individuals

Regardless of your team/org structure, it is important to look after yourself. This may require courage in an organization that isn’t supporting you appropriately. Even if you feel powerless to change anything for the organization the following approaches will allow you to regain some semblance of control over your time . Depending on your organization’s culture these changes in your approach will likely spur conversations with your colleagues about how communication impacts your capacity. Model the way. You may be surprised by the results.

Don’t accept meetings unless there’s clarity for you on how they will help fulfill your priorities and fit within your capacity. Be as disciplined as you can with declining meetings and let the organizers know why.

Question whether the purpose of the meetings you want to convene can be achieved efficiently without meeting.

Don’t convene meetings without providing clarity on the purpose of the meeting. Be clear about who needs to attend and why. Put some thought into an appropriate duration to achieve the purpose.

If you receive a meeting at a time for which you are already busy, decide immediately on the relative priority of each and immediately decline (with a response describing why) the lesser of the two to give the organizer time to reschedule.

Be clear about why YOU would put someone on the To: vs CC: lines of an email. Engage in this discussion with your peers.

Modelling these behaviours can start the process of shifting the organizational culture.

For Teams

Regardless of team structure (project, functional, component, or product-based) simply discussing working agreements can make a huge improvement in most organizations. You may not be able to control how people outside your team try to interact with you, but you’ll reduce the noise inside your team.

Set aside some time regularly to have conversations as a team, about how you use communication tools, how and why we meet, and what works and doesn’t work for your team. Include this time in your team’s capacity.

Create working agreements (including communication conventions) which will set up behaviour shifts that can align your culture with agility.

Make your team priorities and dependencies visible so that team members have a tangible way to prioritize communications.

Modelling these team behaviours further nudges the organization toward a more agile culture.

For Organizations

It’s important that leadership model the behaviours they want to see throughout the organization. Everyone’s time is valuable.

Create organizational support for teams to focus.

Make organizational priorities visible so that teams have a tangible way to prioritize their communications and other efforts.

Create organizational communication conventions and mechanisms that help teams collaborate where necessary.

Educate people and teams in the tools of communication and how they apply to organizational norms.

Model the way, from the highest levels in the organization, for teams and individuals to see.

These are just a few of the approaches I’ve been using to help people, teams, and organizations reduce the noise and increase their flow. Starting and following through on any of the suggestions above is not easy. It takes discipline and consistency for real change to take hold. I have seen it happen.

In my final post in this series, I’ll make the case that communication paths within an organization are akin to an organism’s nervous system. We’ll look at the impact of overloading our organizational nervous system and examine some ‘vaccines’ to ward off current and future noise disorders.